When I was in graduate school for my Masters of Divinity degree, I interned at a network of house churches, pastored by my friend Rev. Dave Barnhart. (His book Church Comes Home is an excellent read for anyone interested in house churches and the Christian house church tradition.) House churches are exactly what they sound like: church communities that gather in someone’s home to read scripture, do liturgy, and hear a weekly message together. The bulk of the service involves discussion about the themes of the text and message. And, of course, snacks.

Interning in those house churches changed by perspective on what a faith community could look like. I loved those cozy afternoons wrestling with scripture and sharing laughs in the name of communal salvation. It felt revolutionary.

And yet, the concept is as old as Christianity itself, and may help us understand how important women were in its formation… and how and when men took over.

I wrote last week about Paul. And as much as I don’t think Paul should be viewed as a primary authority in Christianity on par with Jesus, I do appreciate him as one of the foremost early church historians, as his letters give us a direct view of the relationships and dynamics in Christian gathering spaces in the late first century CE.

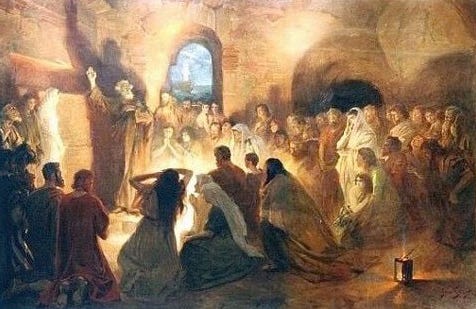

One thing that is exceptionally clear in Paul’s letters--and that we know from other historical documents--is that the earliest Christian churches met in people’s homes. In Paul’s evangelizing travels, he rarely preached in the street. In fact, to do so would have been illegal in many parts of the Roman empire and would have assuredly ended in persecution. Rather, he went to places where he had friendly connections who were willing to host covert gatherings of like-minded people interested in his message. (The fascinating work called The Acts of Paul and Thecla has a great illustration of this.)

Paul stayed in each community for a time to establish it and identify community leaders. After that, he moved on to his next destination and repeated the process. After his leaving, the communities would continue to meet in the host home to avoid empirical scrutiny. This was the norm for Christian churches for the first three hundred years after Jesus’ death and resurrection.

And why does this history matter, beyond general interest?

Because it means that for the first three centuries of Christianity, women were largely in charge.

In the ancient world, the home was the domain of women. Women not only oversaw the running of the home, but they were often more free to speak, even in front of guests. They made all decisions about food, gathering and eating times, and where guests sat and socialized. If a Christian church met in a woman’s home, she was almost certainly involved in its operations and would have been free to influence the messages and topics discussed at Sabbath gatherings. Women’s influence over early Christian gathering spaces would have been at least equal to, if not more than, the men in the room.

And Paul’s writing substantiates this bold claim. His letters are full of missives and statements of appreciation to women, whom he calls “co-workers” and “well known amongst the apostles.” And this is because these women were hosting Christian churches in their homes, creating inclusive spaces for those interested in the Christ movement.

Hosting these gatherings was not simply an act of hospitality; it was an act of radical political rebellion. Christianity was illegal during this time, and known Christians were often persecuted by the Roman Empire. And yet, week after week, these courageous women opened their homes, in direct defiance to the oppressive threats of their government, knowing that they and their families could be persecuted if discovered.

These house church gatherings differed greatly in structure and tone than the church services most of us are familiar with today. Typically, the gatherings began with a communal meal, overseen by the women of the community. Then the small congregation would gather to hear the reading of scripture and a short “message”--something akin to a homily or short sermon--from a member. Then the bulk of the gathering, which could last hours, consisted of lively theological discussion by all community members, male and female, young and old alike.

This is the type of service I led when I interned with a house church network a few years ago, and I can tell you from firsthand experience that one’s relationship with scripture and worship differs remarkably in this kind of space, as opposed to a sanctuary with a pulpit and pews. First, hierarchy amongst the community virtually disappears. While one member may shepard the service, all voices are heard equally. Second, there is far more room for questions and the sharing of different viewpoints; in fact, that’s the whole point. No one person stands in a pulpit, elevated above the congregation, making authoritative declarations. Rather, the community itself is the authority, wrestling with what faith might mean today.

And this wasn’t some brief trend in early Christianity. It was the norm for three centuries. Three hundred years in which women’s voices shaped not just church gatherings but its very theology and practice. Three hundred years in which women were equals to and leaders of men in the burgeoning Christ movement.

So what happened?

Longtime readers know that the answer to “What happened?” is most often, “The Roman Empire.”

In 380 CE, Christianity became the official religion of Rome, thanks to Emperor Theodosius I and the Edict of Thessalonica. Prior to this declaration, Christianity had become increasingly influential in Roman society for the last century or so, with local and regional persecution laws falling out of favor and often being abolished entirely. As Christianity became decriminalized, Christians began to emerge from their home-based gathering spaces and worship, preach, and teach in public.

There was one major catch to this increased visibility: While homes were the domain of women, public life was the domain of men. Women were discouraged from--or even forbidden from--speaking in public. They had little to no say about how public gatherings were structured and virtually no voice in theological conversations or the shaping of doctrine. As influential as they were in home churches, they were all but invisible in public Christian gatherings. And we know what happens when women’s voices are silenced.

Patriarchal control of the Christian church began when its gatherings moved out of the home and into the public square.

While we know the Roman Empire made a concerted effort to erase women’s influence from Christian history--such as discarding Mary Magdalene from the narrative--I truly don’t believe that average Christians considered the implications of the movement from home churches to open gatherings. I’m sure that, for them, it felt positive and hopeful to know they could worship, preach, and evangelize safely without fear of persecution.

And yet here we are, centuries later, with women still trying to reclaim their voices as the leaders and theological authorities they were once known to be.

As the Divine Feminine reawakening of the twenty-first century charges forward, we are seeing a return to more intimate faith gathering spaces, with folks creating inclusive and self-governing communities where they can practice their beliefs outside the confines of patriarchal institutions. I find this reclaiming movement hopeful, as it allows for the practice of authentic faith in non-hierarchical settings.

And yet the solution to the silencing of women’s voices is not to stay entirely home. Home and home-based gatherings as refuge, yes, but it is far past time for women’s voices to be heard in the streets.

And that is why I find movements such as public theologians--of the progressive, deconstructionist variety--on social media so hopeful. Many of these women, queer folks, and allied male theology teachers and content creators are proudly proclaiming our forgotten truths in the largest public square yet available, looking Empire directly in the face, refusing to ever be silenced again.

May their--and our--voices ring out for all those who could not speak in the streets for so many years. And through our words, may what has been hidden for so long be revealed once again.

Thank you for reading! Next week, we’ll look at the controversial figure of Peter. Was he really “the first Pope”? And what would have happened if Mary Magdalene had one the battle for control over the early church over him? Come back next week, as we explore one of the most influential (and perhaps problematic) men of early Christianity.

"They were serving revolution disguised as hospitality." This line gave me chills! Yes. This is exactly what I think of when I think of the women of early Christianity. Quiet, bold revolutionaries moving powerfully in the spaces they had. So beautifully said!

Ah, now here is the sauce no one talks about: the original church was not a giant echo chamber of dudes pontificating behind a pulpit. It was a radical women-led, snack-fueled think tank in living rooms where everyone had a say and no one dared claim divine monopoly on truth.

Women hosting these gatherings were not just serving food; they were serving revolution disguised as hospitality. They held sacred spaces where faith was wrestled with like a wild animal, not tamed into a predictable sermon. And they did this while dodging the Roman Empire’s wrath like spiritual ninjas.

Then, just as Christianity got official and the velvet rope of patriarchy dropped, women’s voices were hustled out the door to make room for empire-approved male authority. Homes became hushed, and the streets where truth belongs became a boys’ club.

Fast forward to now, and the Divine Feminine is rising like a phoenix, crashing patriarchal gatekeeping with fierce, unapologetic voices on social media’s largest public square. This is the real church—raw, inclusive, messy, and loud.

So bring your snacks and your sass. The revolution started in the kitchen and it is moving to the streets. Time to reclaim the pulpit and the mic alike.